Last week I had the great pleasure of serving as one of 12 independent experts at the Hague Institute’s Global Oceans Governance conference. The event, held in The Hague, was co-sponsored by the Observer Research Foundation (New Delhi) and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Last week I had the great pleasure of serving as one of 12 independent experts at the Hague Institute’s Global Oceans Governance conference. The event, held in The Hague, was co-sponsored by the Observer Research Foundation (New Delhi) and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Altogether participants – academics, policy-makers and practitioners – from over 12 different countries attended the two-day event tasked with contributing towards the Hague Institute’s Global Oceans Governance project. The project has two aims:

- To provide actionable policy recommendations for overcoming collective-action dilemmas that stymie governance efforts in the domain of oceans governance.

- To identify general lessons for good global governance that can be applied in other domains as well.

The papers presented at the conference were wide-ranging in their focus. Panels examined the Maritime Ecology, Blue Growth, Sustainable Development, Governance Lessons from the fight against Piracy and Holistic Approaches to Global Oceans Security and Governance. I sat on this last panel and presented the first draft of my paper ‘Mapping Maritime Security: a Small Island Developing State perspective?’ alongside colleagues discussing the Arctic and ‘whole-of-government’ responses to Maritime Security respectively.

My paper encapsulated an initial written output in a new research project for me examining the maritime security considerations of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), specifically in relation to port and coastal security and in the context of the challenges posed by maritime crime. This is a project I commenced last summer with a Coventry University pump-prime grant that facilitated a research visit to Mauritius in August 2015.

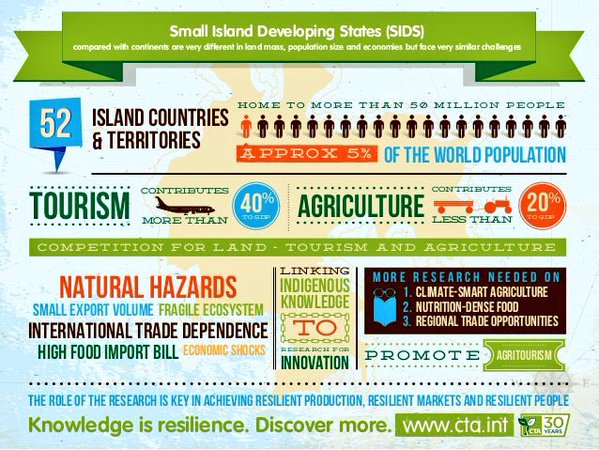

The project stems from my fascination with the way in which Island states relate to and manage their maritime domain. I am particularly interested in the way those states with fewer resources undertake these processes and how they confidently and effectively build capacity in maritime security. For those interested in the importance and needs of SIDS, I can do little better than direct you to the below illustration, which I re-tweeted a couple of weeks ago.

My paper encapsulates a content analysis of the way in which SIDS publicly articulate their maritime security needs within the broader sustainable development agenda. Building on the more comprehensive definition of maritime security that I embrace, I chart the threats which SIDS highlight and seek to note trends over time. Going forwards I will extend this content analysis to determine regional distinctions. The paper’s focus on the public articulation of threats emerges out of a starting premise that it is only with greater clarity over the way in which SIDS conceptualise their maritime security that we can move forwards to better understand maritime security policy and associated security practice relating to these states, alongside the role of SIDS vis-à-vis efforts to improve oceans governance as a whole. I will be writing more about my work on SIDS in an upcoming Maritime Security Briefing, published by the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations.

My paper encapsulates a content analysis of the way in which SIDS publicly articulate their maritime security needs within the broader sustainable development agenda. Building on the more comprehensive definition of maritime security that I embrace, I chart the threats which SIDS highlight and seek to note trends over time. Going forwards I will extend this content analysis to determine regional distinctions. The paper’s focus on the public articulation of threats emerges out of a starting premise that it is only with greater clarity over the way in which SIDS conceptualise their maritime security that we can move forwards to better understand maritime security policy and associated security practice relating to these states, alongside the role of SIDS vis-à-vis efforts to improve oceans governance as a whole. I will be writing more about my work on SIDS in an upcoming Maritime Security Briefing, published by the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations.

Ultimately the conference reminded me of the large number of individuals and organisations with vast knowledge of, and huge commitment to, enhancing our Oceans’ wellbeing. While the topics discussed were wide-ranging, they allowed all the participants to gain new insights, highlight research synergies and recognise best practice. I left the conference ever more convinced that if we are to ensure that the potential of our Oceans is to be sustainably managed for the benefit of as many people as possible then good governance is of central importance.

As we all reflected at the end of the conference on our recommendations for the future I flagged up two words – DIALOGUE and EDUCATION. It will only be with greater and more regular dialogue between different communities, working on different issues, that we will break-down barriers and build workable policies. Here I would like to think Universities, especially those with an interest in applied research such as Coventry University, are well placed to act as a facilitator between academia and practitioners. This is the task that I enjoyed the most during our recent Economic and Social Research Council funded seminar series on the Sustainable Development – Maritime Security relationship.

Moreover, if we are to truly ensure our Oceans function effectively for generations to come we need to expand the educational opportunities for individuals, young and old, to tap in to the energy I witnessed and the kind of ideas I heard at this conference. Education is deeply empowering and the more people that gain knowledge about our Oceans – the threats to them and ways to protect them – then over time we will build an ever larger community who will not only hold political leaders to account, but who will themselves stand ready to get involved to build a brighter future.

If you have any questions or comments on this blog post please get in contact with me either via the comments box or by email.